‘From necessity to narrative’: The History of Letters

By Anya Berg, Soha Bassam Mohammad G E Kassab, and Imogen Sykes

Edited by Naomi Adam

Ahead of the imminent release of The Letters Page Volume 5, members of the web and production teams are taking a closer look at some of the letters that made it to print. Their reflections offer a sneak preview of the pieces included in the new edition and the wide-ranging themes they explore. Today’s article is inspired by Jaseem Al-Ali’s nod back to the very first clay-carved letters of Mesopotamia. Writing from Baghdad, the heart of Ancient Mesopotamia, Jaseem reflects on the historic tradition of human correspondence.

To write is to push back, however gently, against time. Think of a letter as an act of defiance. From the first marks carved into clay, humans asserted that thoughts and ideas must outlive the thinker, and since then, every stage in the history of writing has pursued the same longing: to anchor the fleeting motions of thought.

Letter-writing originated in Mesopotamia, often dubbed the ‘Cradle of Civilisation’, which we know as modern-day Iraq. It was a time of human innovation, including the conception of writing – 3500 BCE was a period in which civilisation flourished. While their ancestors may have been fighting to secure food and shelter, the scribes of Mesopotamia pursued a different kind of struggle: the preservation of thought. Letters allowed humans to record achievements and fulfilled our inherent desire for socialisation by allowing a new medium to communicate.

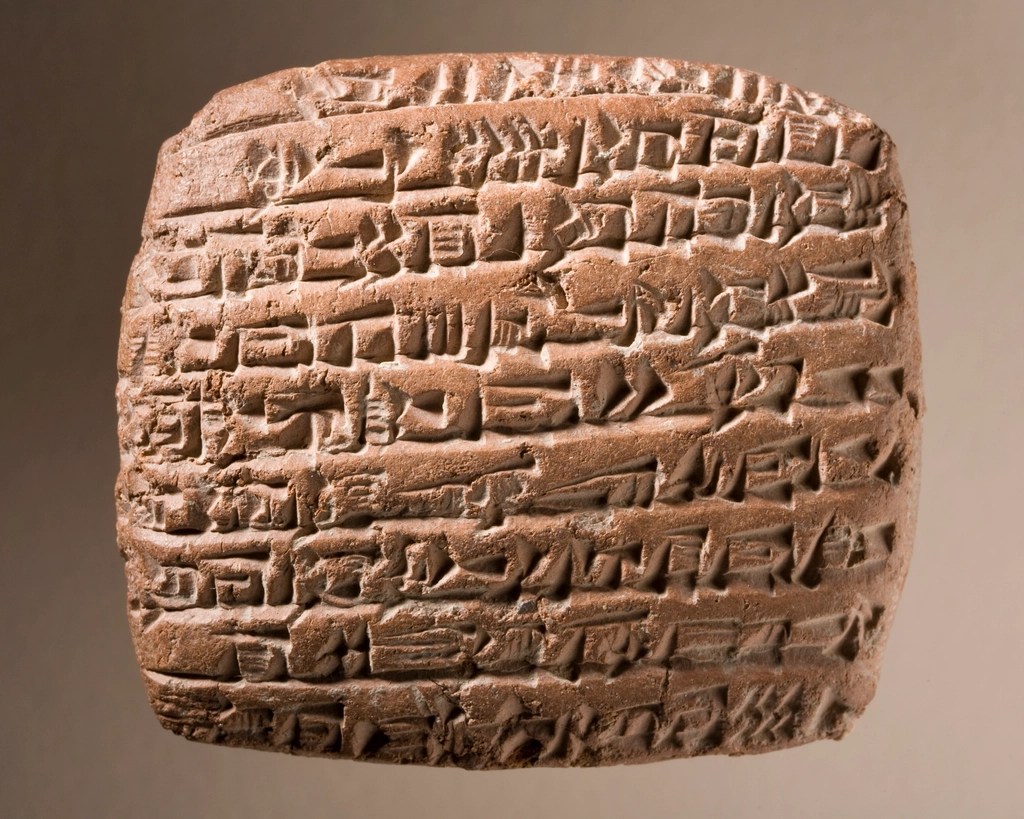

The first writing system was known as Cuneiform, developed around 3100 BCE and deriving from the Latin word cuneus, which translates to ‘wedge’. Visually, this is apt; the stylus used imprinted wedge-shaped impressions into soft-clay tablets. In its earliest form, writing was composed with pictographs, simple pictures representing objects – for instance, a fish symbol for a fish. The system then evolved from ideograms to phonograms, which are symbols representing sounds and syllables. Phonograms are the closest phonetic symbol to what we know today – a precursor to letters of the alphabet.

Cuneiform morphed into cultural markers; the earliest style of recorded storytelling, enabling society to preserve abstract ideas, and articulate emotions.

In early civilisation, the purpose of letter-writing extended far beyond communication; it served as a pivotal tool for record-keeping, administration and the promotion of culture. Writing emerged as a practical necessity: it allowed people to keep track of agricultural produce and ensure trade transactions were recorded accurately. Court proceedings could be inscribed, documenting disputes, judgments and fines. Yet, at the other end of the spectrum, writing was arguably one of the earliest forms of artistic expression – Cuneiform morphed into cultural markers; the earliest style of recorded storytelling, enabling society to preserve abstract ideas, and articulate emotions.

Since this Ancient period, the letter has undergone its fair share of changes. In the medieval period (5th – 16th centuries), letters retained an administrative purpose but were often used for treatises or spiritual teachings too (particularly in the early medieval period before the 12th century). Due to widespread illiteracy, letters were usually composed by a scribe. Scribes were not just essential for simple transcription, but also for their penmanship; a different script communicated different emotions and intentions, and, for those who could write for themselves, revealed much about the author’s identity and status. In Europe, letters were delivered via a third party who, in the case of an illiterate recipient, might have also read the contents aloud. In Arab communities, however, this third party might well have been airborne, as carrier pigeon services were the established system of delivery.

The reign of Charles I marked more significant changes to the letter in England; it became the main source of political documentation, and the circulation of letters broadened under the King’s extension of the royal mail services to the public, thus establishing a postal system. This system required payment from recipients, however, and so letters were still confined to the wealthier in society. The 18th century saw experimentation with the letter form through epistolary fiction – a rising genre connected with the conception of the novel. By the Victorian era, the letter had shed its collaborative origins, becoming the more private, two-way exchange of the personal, intimate correspondence, we are familiar with today.

Many factors, from changing conceptions of the self to advances in writing technology, have shaped the letter’s development from its original tablet-form. Yet, in turn, letter writing has shaped society: by preserving knowledge and stories, letters aided humanity to achieve self-actualisation, paving the way for the legacy to embed itself in our society and future generations.

To trace the origins of letters is to trace humanity’s evolution, from necessity to narrative, from survival to expression.

To trace the origins of letters is to trace humanity’s evolution, from necessity to narrative, from survival to expression. Letters serve as proof that human culture hinges on exchanged words between people and the faith that understanding can cross time – something illuminated in the upcoming print issue of The Letters Page, in collaboration with UNESCO Cities of Literature. As part of this collection, Jaseem Al-Ali writes from the country of the letter’s origin: Baghdad, Iraq. Jaseem’s submission ultimately highlights that, even as the world changes and reshapes itself around us, human correspondence has and will always remain immutable.

The Letters Page team are back in the office, and ready to read your real letters again. We publish stories, essays, poems, memoir, reportage, criticism, recipes, travelogues, and any hybrid forms, so long as they come to us in the form of a letter. We are looking for writers of all nationalities and ages, both established and emerging.

Your letter must be sent in the post, to:

The Letters Page, School of English, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK

See our submissions page for more information.