‘Yours, in fragments’: The Contradictions of Correspondence

By Soha Bassam Mohammad G E Kassab, Imogen Sykes, and Anya Berg

Edited by Naomi Adam

The correspondence below collates fragments from several writers. Each reflects on the act of letter-writing, from its performances and paradoxes to its intimacies. Together they form a composite collection, narrating interactions between selves across time.

If these words find you, they’ll arrive already edited by my idea of you.

Which is to say, every letter starts with an unfinished version of the writer. When we write to someone else, we become the person we imagine ourselves to be in that person’s eyes. After all, to write a letter is to perform the self in ink. We structure ourselves through a choreography of tone, through composed and sensitive metaphors, through deliberately messy thoughts, and this performance cannot be complete without the reader’s silent presence from the other side. Therefore, letter-writing is not merely an act of communication, but an act of self-construction that exposes how ambiguous the divide is between performance and honesty.

To write a letter is to perform the self in ink

Since it sits somewhere between confession and performance, the letter speaks into the silence, yet always with someone listening and observing. Whether a response is immediate or prolonged, it still defines the very flow of what is written. Letter-writing is a transformation of dialogue into monologue, but delivered with complete self-awareness. It is like rehearsing a conversation in solitude. Every pause becomes a comma, every hand gesture a charming phrase, and the tone adopted becomes a costume the writer slips into, not to deceive or trick the reader, but rather to preserve the bond across distance.

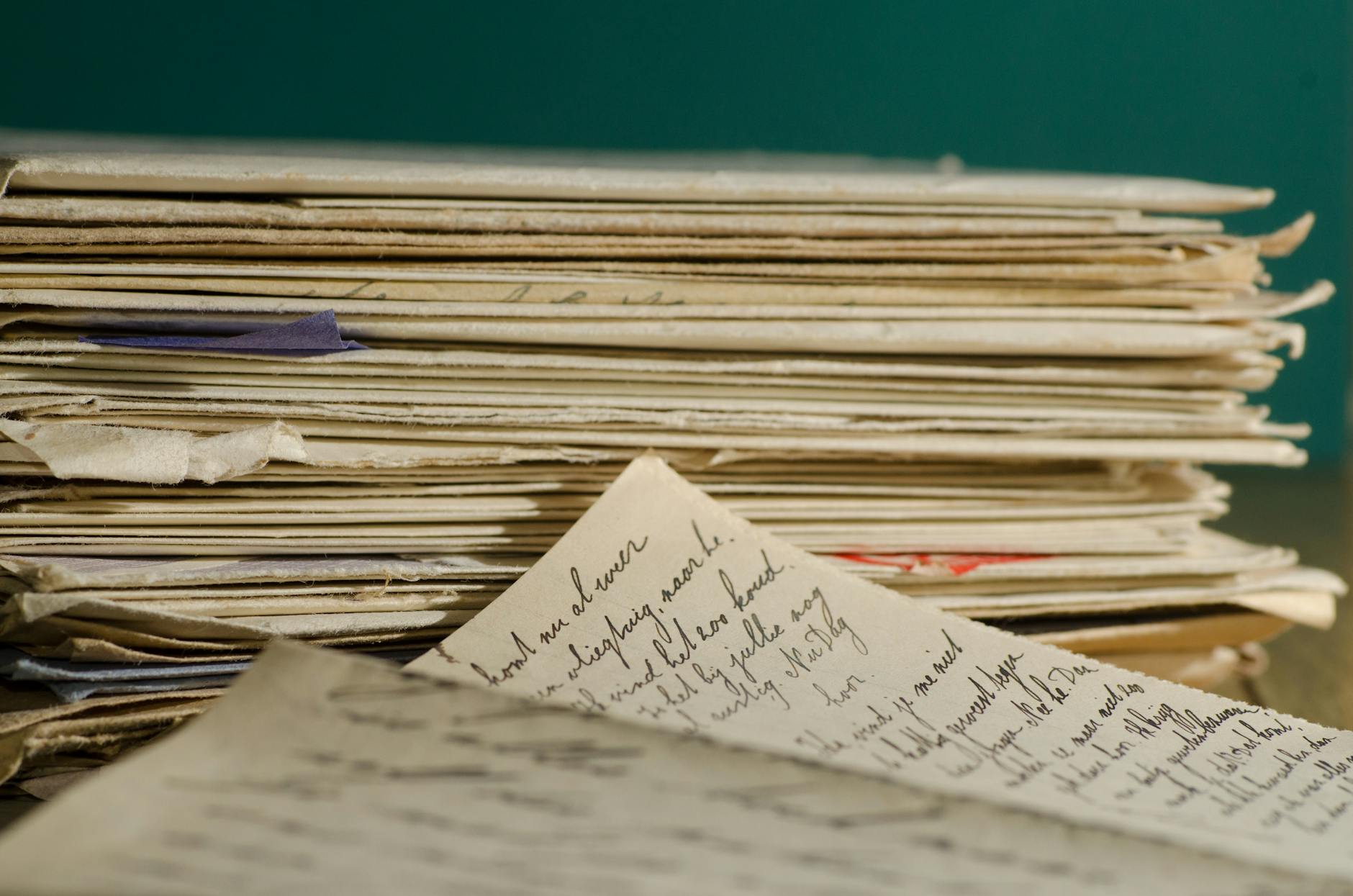

Even the physical appearance of a letter carries this performance. Handwriting, that intimate declaration of the body, is used as an extension of how someone speaks. Hasty handwriting expresses urgency or desperation, whereas careful loops and curves between letters indicate diligence and serenity. Handwriting anchors emotions in a tangible form, and it betrays vulnerability precisely because it cannot be perfectly edited. In a way, though, this vulnerability is calculated. To strike the perfect chord, the writer rewrites opening lines and erases sentences that are too revealing for their liking. Such decisions are what highlight the contradictory nature of letters: they seem raw and natural, but in reality are meticulously planned and laid out.

If you are reading these thoughts, know that my self is in them, if only a fragment.

Letters are mirrors, reflecting our selves. Consider how a mirror glimpses you all dressed up, outfit meticulously planned, and yet it has already witnessed you piece this together; your raw, unmade-up, undressed image sat before the glass pondering how to present yourself at the upcoming job interview. Both are you, created by you, and are in equal parts your self. However contradictory, the mirror sees both, and so it is with a letter.

But the self who prepared for that interview differs from the one that gets the job; from one moment to the next, you are not the same. Just like this, we constantly change, flecked with minuscule new marks – a new mark for the coffee we bought with a friend last Friday, a new etch carved for the extra hour we stayed up to finish an assignment last night. Never in one moment are we our full selves, but merely a fragment.

The more letters we write, the more moments we capture, and the more fragments we preserve, the closer letters come to revealing our complete identity.

Letters, too, capture this: momentary objects, written in a sliver of time, by a fragment of ourselves which we preserve in that sweep of the pen nib. One letter alone is not a demonstration of our whole ‘self’. But the more letters we write, the more moments we capture, and the more fragments we preserve, the closer letters come to revealing our complete identity.

Letters become our own personal archives, splintered across time and space. Here, I leave you with a splinter of me.

If the person you were when you began reading this sentence no longer exists, how do you ensure permanence through correspondence?

Signing off a letter suggests it has reached an end. But they don’t really ever end. They simply pause. Each piece is a fragment pretending to be whole – an incomplete record of who we were when the ink dried. Between one letter and the next lies a temporal purgatory, if you will – a stretch of time, long enough for us to become someone else. Each exchange takes place between two changing selves; every letter is written by, and addressed to, a new person entirely.

Humans have an innate tendency to try to rationalise the world around us, but not everything has to make sense. Once we accept that, we can simply enjoy the art before us – whether it’s the natural world or a creative work. Sometimes, searching for deeper meaning can distract from the simple act of appreciation. When letters are collated, we are wired to try to make sense of them as a unified whole, searching for coherence in their fragmentation. We dig for a story, clarity, a consistent self. However, that coherence we’re so sure of is an illusion. Letters are written across time; they are composed from various moods, identities, relationships and moments of self-understanding. All that truly exists is fragmentation, which ought to be embraced. Letters are shreds of many selves across time, written in absence – each filling a gap, reaching toward someone not there, responding to an earlier self already changed.

When letters are collated, we are wired to try and make sense of them as a unified whole, searching for coherence in their fragmentation. However, that coherence we’re so sure of is an illusion.

If letters preserve versions of our past selves through carefully chosen words, the way we communicate digitally does something similar. We produce pixellated remnants of who we were, dispersed across inboxes and texts. Emojis express complex emotions – simplified gestures standing in for the depth once conveyed by full sentences, yet still carrying traces of intimacy and intention. And whether preserved in paper or pixels, the recipient pieces together impressions which can’t ever fully be constructed into wholeness.

So, we ask ourselves, which versions of us survive in the archive – the ones we intend to send, or the ones we drafted first? Every fragment is filtered through choice and chance, leaving us to wonder whether the selves we leave a written record of are authentic reflections or carefully curated ghosts – distant echoes of who we wished to become.

Yours,

In fragments,

The Letters Page team

The Letters Page team are back in the office, and ready to read your real letters again. We publish stories, essays, poems, memoir, reportage, criticism, recipes, travelogues, and any hybrid forms, so long as they come to us in the form of a letter. We are looking for writers of all nationalities and ages, both established and emerging.

Your letter must be sent in the post, to:

The Letters Page, School of English, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK

See our submissions page for more information.

One thought