Can Books Bridge Nations?

By Elodie Edwards and Zoe Lidbury

Edited by Naomi Adam

Ahead of the imminent release of The Letters Page Volume 5, members of the web and production teams are taking a closer look at some of the letters that made it to print. Their reflections offer a sneak preview of the pieces included in the new edition, and the wide-ranging themes they explore. Today, we discuss pseudonyms, the forces that shape our reading habits, the debate over separating art from artist, and the Ukrainian letter-writer who ties it all together. Our feature has been inspired by an original letter from Oksana Danchuk, sensitively translated from the Ukrainian by Nina Murray.

Oksana Danchuk is a Ukrainian playwright based at Lesia’s Theatre in Lviv. She is writing to The Letters Page to us during the holidays that follow the conclusion of the theatre’s season. Oksana demonstrates a gift for letter-writing – her talent is clearly not limited to writing stage material. However, she suggests that her theatre critic friend Oleksiy would write a much more interesting letter. The thing is, Oleksiy is currently serving in the military – he’s been there a year and is still waiting to be granted his first leave.

His involvement in the war might decrease the palatability of a letter from him for many people. An author’s politics, nationality, or social standing can shape how their work is received – or whether readers choose to engage with it at all. In times of conflict, allegiance can determine whether a book is accessible or deemed acceptable. Seamus Heaney, for example, suppressed ‘The Road to Derry’, his poem addressing Bloody Sunday, for many years, fearing the risks of releasing such charged material amid deep political division. However, Oksana argues that it is this experience on the front-line that makes his voice so important.

A writer’s personal experiences inevitably shape the stories they tell, but dominant voices often drown out the rest. This imbalance can create an echo chamber, obstructing readers from encountering alternative perspectives. Just as a casual reader might be drawn to a bright cover, many of us gravitate towards familiar names – sometimes out of bias, sometimes out of comfort, and sometimes, consciously or not, out of prejudice.

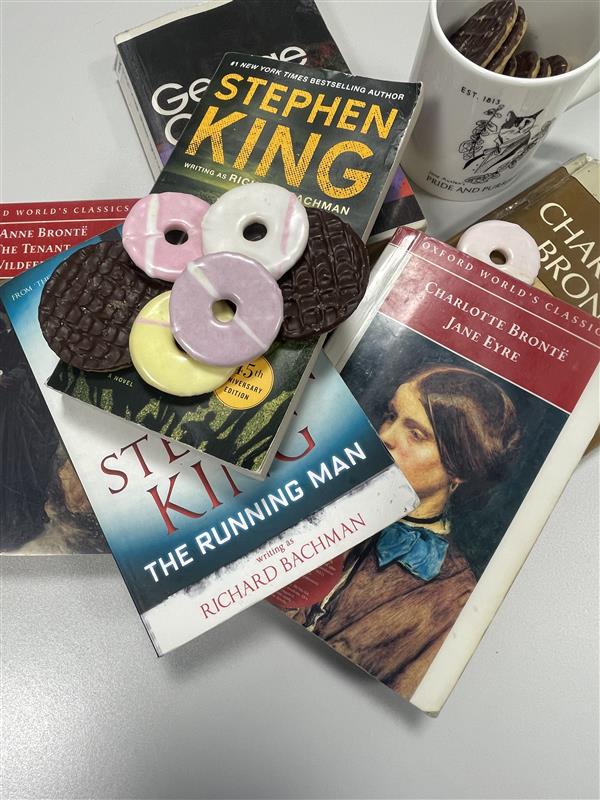

Arguably, anxieties around such prejudice gave rise to a history of concealed identities within literature. Some of today’s best-known authors began their careers under assumed identities – and some never shed these disguises. For many, pseudonyms were born from necessity, a way to circumvent social constraints such as class, gender, or the political climate. The Brontë sisters renamed themselves Currer, Acton, and Ellis Bell, fearing that their work would be dismissed because they were women. George Orwell (born Eric Arthur Blair) adopted his pen name to shield his family from the potential backlash of his politically charged writing. In contrast, modern writers often turn to pseudonyms not out of fear, but curiosity. Stephen King, for instance, wrote as Richard Bachman to test whether his success came from literary skill, or merely name recognition. What was once a tool for survival has, in many cases, become an experiment in artistic freedom or aesthetic preference.

This leads naturally to a very topical point of contention – can we, and should we, separate the art from the artist? Some argue that literature should be taken at face value; others believe a creator’s identity is inseparable from their work. This insatiable desire to learn more about the person behind the pages is timeless – but whether that curiosity enriches or distorts our reading is another matter entirely.

At the end of the day, whichever side of the argument you fall on, the joy and value of reading remains undeniable. It seems unnecessarily cruel to restrict what others can read when books have such a remarkable power to bring people together. The global reach of certain beloved titles – translated into dozens of languages and cherished across cultures – reminds us that no matter where we come from, we are all drawn to stories.

The magic of words lie in their multifaceted, multifarious nature: the same sentence can speak differently to every reader, and two authors can wield the same language in entirely unique ways. Any one book is not like another; as Oksana Danchuk writes:

There are books that help [one] understand reality, and books that help [one] to escape it.

A good book can offer solace from daily demands, peace for an overactive mind, or simple pleasure – especially with a biscuit and a cup of (Yorkshire!) tea. But for Danchuk, a good book is more than a humble comfort. It has the potential to heal fractured nations, unite divided peoples, and remind us of our shared humanity by offering new perspectives.

I do believe that some nations, if they read more books from other nations, would feel less inclined to attack their neighbours with rockets.

Oksana is featured in The Letters Page’s latest release, available to buy here. This publication contains her completed letter, alongside nine others from UNESCO Cities of Literature around the world.

You don’t need a second identity to write to us! The Letters Page team are back in the office, and ready to read your real letters again. We publish stories, essays, poems, memoir, reportage, criticism, recipes, travelogues, and any hybrid forms, so long as they come to us in the form of a letter. We are looking for writers of all nationalities and ages, both established and emerging.

Your letter must be sent in the post, to:

The Letters Page, School of English, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK

See our submissions page for more information.