Ella Minnow Pea: Censorship and Letters

By Amy Child

Edited by Annabel Wearring-Smith

“Words upon words, piled high, toppling over, thoughts popping, correspondence and conversation overflowing.” Mark Dunn, Ella Minnow Pea

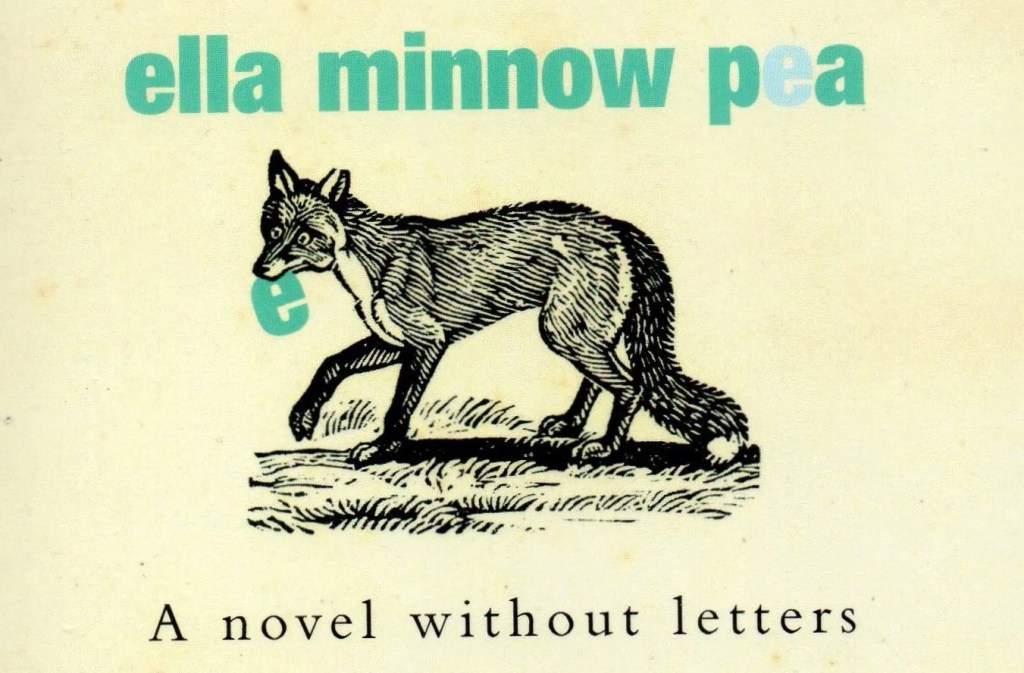

What if restrictions were placed on language? If certain letters of the alphabet were banned, and all written correspondence scanned for their forbidden use? These are the questions explored by Mark Dunn in his 2001 novel Ella Minnow Pea: A Novel in Letters.

Letters are central to the novel in both senses of the word; it is epistolary (written as a series of letters) and progressively lipogramatic, as Dunn drops ‘banned’ letters from his writing one by one. In it, a fictional island called Nollop is beset by a totalitarian government that enforces rigorous censorship, punishing those who use forbidden letters with lashing, stocks, and even banishment. To counter the censorship they face, Ella and her companions begin a project called ‘Enterprise 32’, which aims to find a pangram of only thirty-two letters. This is to disprove the government’s belief that Nevin Nollop (the man who supposedly came up with the pangram ‘the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog’) is sending divine signals to remove letters from the lexicon by dropping them off his statue. Dunn’s playful literary technique and the book’s nursery rhyme title and fable-like quality, contrasted with the decidedly more serious subject at hand, results in absurdist political satire.

I read Ella Minnow Pea a few years ago now, but the story has always stuck with me. For, whilst Nollop is a fictitious island, censorship has been all too real in the literary world. The recent controversy over supposed changes made to Roald Dahl’s beloved children’s books got me thinking about the book again. Dahl’s British publisher, Puffin Books, made news headlines with their decision that gender-neutral terms will be swapped in and insults derived from physical appearance will be removed from the beloved books. A spokesperson for the Roald Dahl Story Company stated: “we want to ensure that Roald Dahl’s wonderful stories and characters continue to be enjoyed by all children today”, but are these tweaks to Dahl’s stories harmless, or are they, as author Salman Rushdie declares “absurd censorship”? Debate surrounding whether texts should be tampered with or left untouched continues to provoke. Language, past and present, cycles through constant- and conflicting- conversations.

An example that blazes to my mind is that of Nazi book burnings: the literary purge of any written texts deemed ‘un-German’. A brutal public display that sought to “purify” the German language and literature with flame. The uniting force of language was divided into two groups: the worthy and the unworthy. Unsurprisingly, many of the burned texts were by Jewish authors and others who failed to fit Nazi ideologies.

However, not all acts of censorship amount to the spectacle of burning books. Governments around the world, throughout time, have metaphorically blotted words and torn out pages. Looking at the ‘Best Banned, Censored, and Challenged Books’ on Goodreads list suggests a trend in banned books; the books which have an embargo placed on them contain criticism that challenges the social order in some way. This begs the question: why do governments want to prevent people from being influenced by what they read? Surely, influence is the power of words, and perhaps the danger of them, too.

Part of George Orwell’s 1984, a commonly censored book which, ironically, warns against censorship, came prophetically true in April 1984, when officers from Customs and Excise raided Gay’s the Word, an independent bookshop in Bloomsbury, seizing thousands of books in a move labelled ‘Operation Tiger’. However, this attempt at censorship, fuelled by a wave of homophobia, was met with a fierce defence campaign. After two-and-a-half years, all charges were dropped, and the books were safely returned. As Dunn says:

“We slowly conclude that without language, without culture— the two are inextricably bound— existence is at stake”

I’ve always considered letters a private, intimate channel of communication, where both sender and recipient have freedom of expression. But this is not the case for Ella and her friends. Dunn shows how, when this channel is intercepted and the privacy of the letter ruptured, the very act of writing and sending letters becomes an act of rebellion. Letters become a way of facilitating freedom of speech.

Letters are not only banned from written communication on Nollop’s shores but from spoken communication too. Under these conditions, the letter, with its capacity for alternative spelling, becomes the most effective form of conveying words otherwise inexpressible. The novel’s characters adapt by finding new ways to communicate, using increasingly creative substitutions for words and letters.

This concept of the lipogram, and self-imposed restrictions, has a rich tradition. A Void by Georges Perec is a famous example of a novel written without the letter ‘E’ (which I’ve used twelve times in that sentence alone). Whilst this might seem trivial, the absence of ‘E’ in Perec’s text reflects the loss and absence integral to his life, as his father died in WW2 and his mother was killed during the Holocaust. Restrictions on language often reflect the far more daunting theme of restriction of freedom – not self-imposed but enforced by others. By asserting his control over language, the gaps in Perec’s text allow more to be said by the absence of letters than by their presence.

What Dunn’s novel proves, in the most empowering sense, is that communication finds a way. Even when limited to only five letters: LMNOP, Dunn’s words transmit meaning to the reader. They are more than the sum of their parts. The novel’s linguistic experimentation invites the reader to view communication from a fresh angle and newly appreciate its value. As they say, you never realise what you have until it’s gone.

“Love one another, push the perimeter of this glorious language. Lastly, please show proper courtesy; open not your neighbour’s mail.” ― Mark Dunn

The Letters Page team are back in the office, and ready to read your real letters again. We publish stories, essays, poems, memoir, reportage, criticism, recipes, travelogue, and any hybrid forms, so long as they come to us in the form of a letter. We are looking for writers of all nationalities and ages, both established and emerging.

Your letter must be sent in the post, to :

The Letters Page, School of English, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK.

See our submissions page for more information.

To stay up to date on The Letters Page newsletter publication, subscribe here.