The Art of the Letter

By Maria Rocha

Edited by Naomi Adam & Amy Plant

Letter writing is, and always has been, more than words on a page. Whether the product of ink on paper or typed on a keyboard, a letter expresses something deeply personal and acts as a medium that connects us to ourselves and others. Clive Cass’s recent letter to The Letters Page, inspired by a virtual workshop on letter writing hosted by the National Gallery, stood out not only for its content but also for what it revealed about the letter writing process. It captures how putting pen to paper can be a journey of self-discovery and reflection.

Although Clive has long been drawn to art history, he reveals in his letter that writing has not always been an easy form of expression for him. Growing up with dyslexia, he faced early struggles with written language, which were subsequently accompanied by feelings of shame. However, through the seemingly small act of writing a letter, he has demonstrated a way to overcome these barriers, reclaiming the written word as a tool for connection rather than a source of frustration. His words illustrate how letter writing is inextricably linked to our innate, fundamental artistic impulse as human beings – that inner urge to translate our emotions and personal experiences into something tangible. Writing, like any artistic act, requires vulnerability and a willingness to confront the depths of one’s experience.

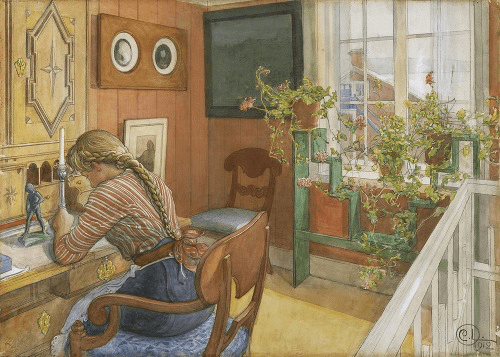

This impulse has been immortalised in art for centuries. Paintings of letter writers often capture the intimacy of the act, depicting subjects lost in thought and immersed in quiet solitude. Such images evoke themes of introspection, secrecy, and emotional depth, reinforcing the idea of the letter as a vessel for personal revelation.

The artistic depiction of letter writing spans centuries. In the 17th and 18th centuries, artwork frequently reflected the intimate and theatrical nature of correspondence. Notably, much biblical artwork from this period features Saint Paul deep in thought with a quill or a binder of letters tucked beneath his arm. These depictions highlight how his epistles to the various communities of the early church were more than mere correspondence – they were foundational texts of Christian doctrine, vessels of divine revelation that are still studied after two millennia. This embodies the power of letters to transcend time and place.

By the 19th century, the portrayal of letter writing shifted from the divine to the domestic, with central themes of courtship, longing, and intimacy. Paintings of this era frequently feature women engaged in the act of writing or receiving love letters, with several sharing the title The Love Letter. This romanticised imagery of women as recipients of letters mirrored societal norms, where courtship, secrecy, and emotional expression were closely interlinked with the feminine sphere.

By the 20th century, the rise of telegraphs, telephones, and digital communication led to a decline in letter writing as an everyday practice. Consequently, its artistic representation also diminished. With the rise of Modernism, Abstract Expressionism, and Surrealism, artists moved towards conceptual ideas and away from realistic scenes, paralleling society’s move away from the written page.

Even as letter writing waned in daily life, artists continued to use letters as an extension of their creativity. Vincent van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo were often adorned with sketches of landscapes and figures, merging text and image to turn even workaday correspondence into a form of creative storytelling. This tradition has continued into the modern era, with illustrated letters in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art showcasing how artists have long viewed letter writing as an artistic endeavour. These collected works prove that the letter itself can be as much a piece of art as the message it conveys.

Beyond their artistic potential, letters have also served as powerful vessels for raw, unfiltered emotion. This is exemplified in the words of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, whose letter to Diego Rivera reveals her process of transforming pain into prose. Her words, written from a hospital room before the amputation of her right leg, capture the emotional force that letters can carry and the deeply artistic process behind them:

‘I’m writing to let you know I’m releasing you, I’m amputating you. Be happy and never seek me again. I don’t want to hear from you, I don’t want you to hear from me. If there is anything I’d enjoy before I die, it’d be not having to see your fucking horrible bastard face wandering around my garden.’

Just as a painting or sculpture externalises emotion, a letter gives shape to personal turmoil, turning it into something tangible and self-reflective. In the digital age, the domination of instant messages and emails has reduced this process to what is often called a ‘lost art’. Clive’s letter reminds us that writing is an intrinsically artistic and expressive act. Whether reflecting divine revelation, romantic longing, or raw emotion, the letter endures as a powerful testament to the depth, power, and artistry of the written word.

We publish stories, essays, poems, memoir, reportage, criticism, recipes, travelogue, and any hybrid forms, so long as they come to us in the form of a letter. We are looking for writers of all nationalities and ages, both established and emerging.

Your letter must be sent in the post, to:

The Letters Page, School of English, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK